In the work Self-Portrait and Other Ruins, artist Ghazal Ramzani inscribes her body into the genealogical continuum of female memory, treating it as a living architecture—a space where the traumas of exile, loss, and transgenerational resistance accumulate. This film functions as a visual-poetic, choreographed essay, where dance is not mere expression but an epistemological mechanism—a mode of knowing that operates beyond language.

Returning to the maternal home, the house of childhood, is triggered by the loss of a foundation: the death of a grandmother, a figure of homeland and country. Entering these ruined topographies of memory is not a return to nostalgia, but an archaeological act. The home becomes an emotional foundation—one that we often forget to feel in the midst of movement. Again and again.

In Self-Portrait and Other Ruins, the subject moving through the corridors of the family home is not merely an identity-bound entity, but a bearer of unspoken and repressed histories. Here, the archive is not a collection of objects, but a vibration of movement—a porous threshold between the personal and the collective. Through choreography, Ramzani destabilizes the linear perception of time: the past is not behind us, but under the skin. Her body becomes a site of enactment for a dislocated past, a haunted dwelling of social ghosts that inhabit the present.

The dancer with closed eyes does not perform memory — she inhabits it. In that space, movement becomes an act of haunting, but also of emancipation. For it is precisely where the languages of the state, patriarchy, and hegemony fail that the body begins to speak. As archive. As affect. As aphorism.

Ghazal Ramzani’s work offers a critique of representation. She rejects the spectacularization of pain and the aestheticization of trauma. Instead, she establishes a kinetic politics of memory — a way for the past not to be depicted but re-enacted through the body. Her art is a feminist intervention in which the genealogy of female laboring experience is not written through narrative, but through rhythm, pause, silence, and contact with the ground.

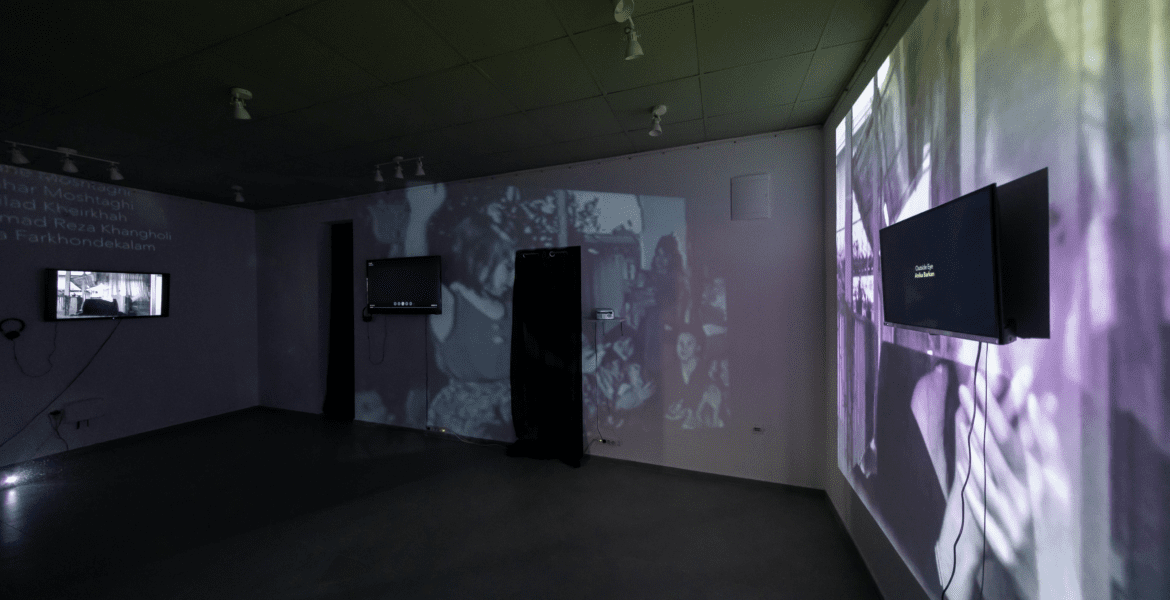

In the spirit of deconstructing postcolonial and exilic narratives, Self-Portrait and Other Ruins opens a space for thinking of memory not as an archive of data, but as a fragmented body — a body fractured by history. This dance does not unfold within a closed choreographic system, but in liminal zones. By entering the space, the audience steps into a singular world of thought, memory, and identity — one that simultaneously pulls them in, dissects them, and stretches them apart.

There is a strange kind of dignity in this work. A heavy poetics. A rebirth.

It does not strive for wholeness, but for the point of rupture.

So — be silent and dance.